Illuminated Flora and Its Magical urroundings, Ernesto Carozzo

Presented by Monira Foundation

Visiting hours: by appointment

Illuminated Flora and Its Magical urroundings, Ernesto Carozzo

Presented by Monira Foundation

Visiting hours: by appointment

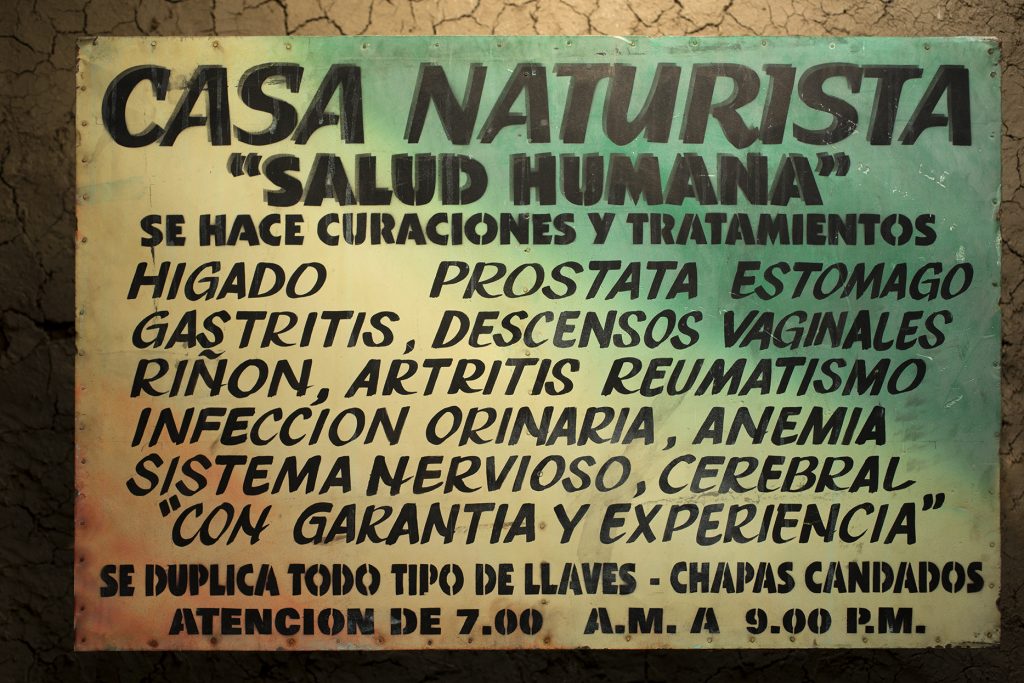

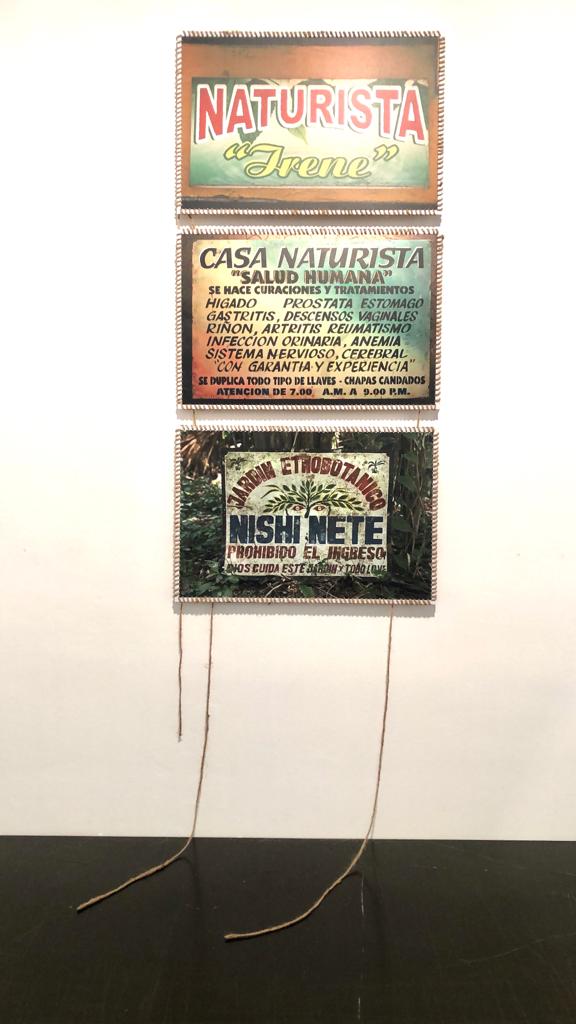

The field of traditional medicine in Peru requires our full attention more than ever before. Not only because those who practice it have been able to cure, surprisingly enough, a number of patients treated by certified doctors to no avail, as no clear diagnostic nor palpable relief came to these cases in the form of medical régimes or prescription of pharmaceutical products; but also ‘gene piracy’ is now in operation by transnational pharmaceutical companies, in surviving natural spaces such as the Amazonian rainforest, to take possession of specific plants, with scarce investment in laboratory research work, upon the basis of extant information about their healing properties obtained from shamans and traditional medicine-men, to rather deviously prepare and produce generic patents on plant genomes, with expectations of sheer profit.

In his early twenties, Ernesto Carozzo Arregui (b. Lima, 1980) became interested in the work, the knowledge and the will to serve others of an Andean shaman or medicine-man. He approached one and asked to remain with him the minimum time required to observe at close hand a dynamics in which plants are extremely valued because of their healing powers and secret roles in a magical world with which traditional medicine in Peru is totally connected. Of this magical key-aspect of shamanism there are still very few studies in our midst (1). Carozzo’s fascination with traditional medicine and the plants that constitute a living pharmacopoeia, sought out in fields, forests, mountains, water courses and lakes, remained intact throughout almost two decades and also accompanied the birth of a new passion for a medium of artistic creation that completed his personal world: photography.

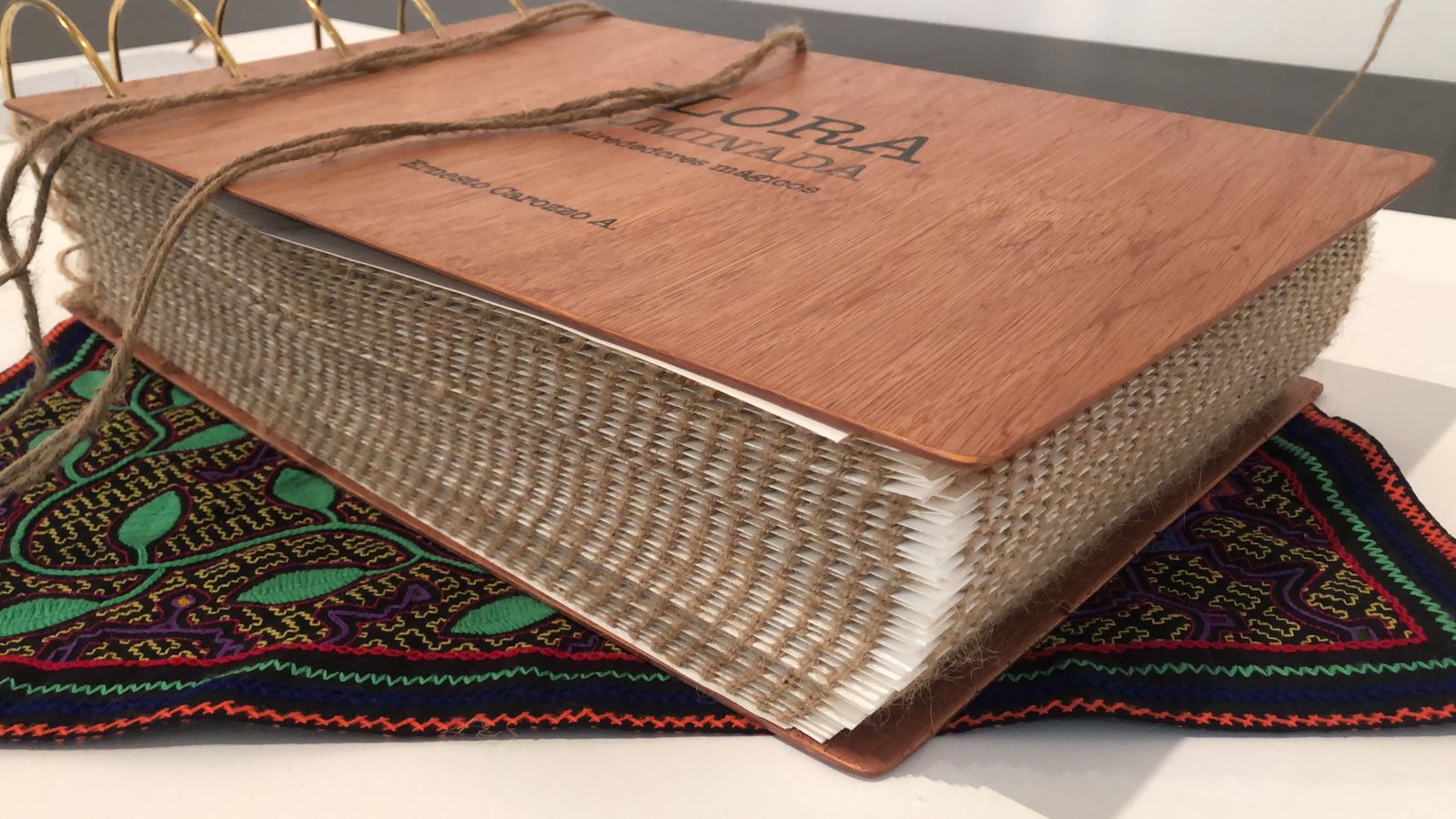

This photo book, manually put together and sewn, is born from those two passions that have been feeding back into one another for a long time. The volume, which at the moment is a unique piece, is conceptually a photographic medicinal herb atlas, in which collected specimens are simultaneously presented to those who are interested in images and their associations, and those interested in the knowledge visually symbolized by the contents as a whole. To facilitate understanding the atlas, Carozzo divides the pharmacopoeia in three, as in the conventionally defined three natural regions in which school geography books used to divide Peru: coast, Andes and rainforest. There are individual persons in association with each of the three. Thus, a woman who sells medicinal herbs in a market in Lima is linked to the coast, and to a particular group of healing plants more frequently used in the region. A well-respected, Andean medicine-man represents the highlands, together with a different set of healing plants used in Andean shamanism. A lady-shaman and her son are linked to the rainforest in the atlas, with the corresponding group of medicinal Amazonian plants frequently used in regional shamanism. In practically every image in the atlas, a hand -right or left- holds a plant specimen, and this visible alliance between human and plant, which could have been a novelty in a conceptual photographic project, awakens in the mind other images, of ancient times, in which significant attributes were carried in the hand by allegorical figures or mythological characters; branches, flowers and fruit, in High Renaissance Europe, still made connection with the religious turn of the imagination of observers-readers.

Where there is definitely an innovative proposal is in the manner in which he decides to give each of the three group visions of plant images a configuration. He discards the geometrical grid pattern -neatly connected with the well-ordered presentation of

equal, or marginally different elements, advanced by minimalism and adopted by a certain kind of conceptual photography at the end of the 20th century–, as model. He follows a personal path that may be pointing, in a way, to the influence of his personal assimilation of the archetypes of Carl Jung. The group from the coast is spatially ordered following a pattern that may allude to a Kero or Inca ceremonial vessel for libations, but also to an hour-glass. The images of plants from the Andes are ordered in the form of a chakana or Andean cross, a pre-columbian symbol. For the set of images of Amazonian plants he adopts the lineal pattern of a fragment of kené, the perfectly fine line drawing that is hand-painted by women of the shipibo-conibo ethnic group on textiles and ceramic objects. The research leading to his choosing non-Western –at least not exclusively Western–, geometric-abstract symbols, introduces another type of visual configuration that could give rise to wall-installations in exhibition spaces, as a non-conventional gesture towards making visible the potential of each pattern and confer upon it an authentic, culturally heterogeneous character. Even as a reminder of the way in which the Peruvian population is an amalgam of nations, that, surprisingly, however, have in common syncretic forms of knowledge, forever intertwined, imbricated. And it is not a matter of seeking out the originally warp from under the Western woof.

However, there is, here, a manifestation of a two-headed epistemological system, through images and through the word that names, contains and comprehends. What Ernesto Carozzo does is recognize equal cultural weight in both, to conjugate them as sustainedly and fluently as he possibly can, and as simply as possible point, thus, to our inheritance as human species: there is no need to relentlessly impose upon what we are used to calling World, as mandate of some form of internalized superiority; we are called upon, rather, to accept and assume our inherent fragility as living beings and survivors, and engage in a labour of concord and correspondences, where we previously only identified discontinuity and division.

Jorge Vilacorta Chávez, August 2022.

Don't miss out on new events, programs, and artist opportunities!